Imagine at the age of 10, your body begins to undergo weird changes. These things start to grow on your chest and you begin to experience unusual feelings. Unsure of the cause/s and how to cope, you run to the one person who have protected you from harm your whole life for guidance – your mother. She has nurtured, guided and protected you. Without her, you are lost in the world.

Now imagine that the same person you have entrusted with your life starts to inflict pain upon your body. She places a stone on the fire and then applies it to the two growing mounds on your chest. Various thoughts run through your head. You begin to think of all the things you could have possibly done wrong to deserve such punishment. The is pain unbearable, but as a child, you have no choice but to obey your elder. You lay flat on your back confused as your mother rigorously applies the hot stone on your chest over and over again. The only explanation given is that what she is doing is for your own good. She is doing this to ensure that boys do not make unnecessary advances toward you, try to take your innocence away and essentially ‘spoil’ you. She also mentions that she too had to undergo the same process at your age. She is thankful for the ostensible benefits it has brought her. She is confident that had she not undergone this process, she would not have been able to attain all she has in life.

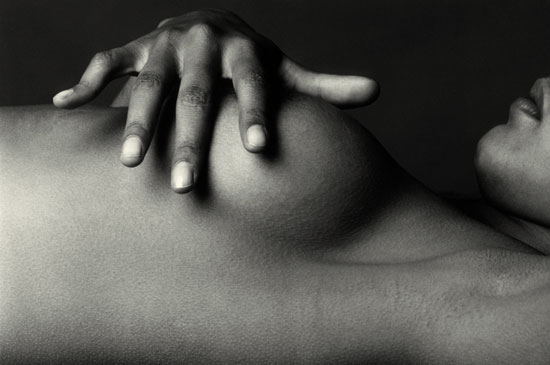

The practice of Breast Ironing is not new. It has been predominantly practiced in the African country of Cameroon for hundreds of years. Other sub-Saharan African countries including Chad, Togo, Benin, and Guinea-Conakry, also practice Breast Ironing in some regions. It entails the use of various objects, including stones, coconut shells, ladles, spatulas, hammers ect, which are placed on a fire, then pounded or rigorously massaged on the breast of adolescent girls. Usually imposed on girls between the ages of 8 to 14, Wamabele ayina is okwakuhloswe njengendlela anciphise umsebenzi wocansi esemncane. The aim of the practice is to flatten/lessen the visibility of a young girl’s breasts, thereby making her less desirable to potential male predators.

RENATA (Reseau National des Associations des Tantines or National Network of the association of Aunties) and German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ) published a report in January 2006 estimating that the practice was most prevalent in 2 areas in Cameroon, the coast at 53 per cent and the north-west at 31 percent. Since then, various organizations advocating for women’s rights have published numerous stories about the practice in hopes of bringing about awareness and calling for its eradication. Many argue that the practice is a violent, senseless act against women and the note repercussions of the practice, including excruciating pain, psychological trauma, destruction of the breast tissue (which is vital to breast feeding), severe scarring and possible cancer.

What I find most interesting about Breast Ironing, is that it is a practice imposed on young women by the women they trust. Like the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM), Breast Ironing is a direct assault on womanhood by other women. One can hardly argue against this stance given that the breast, arguably the most prominent visible display of womanhood, is the target of the practice. While many defend the practice as a way to prevent pre-marital sex, sexual assaults, teenage promiscuity etc., their claims have not been substantiated by empirical evidence. Others who have defend the practice of Breast Ironing as a generational practice that is integral to the preservation of culture, fail to demonstrate the cultural ‘benefits’ the practice has to offer.

I am a strong proponent of culture and its maintenance. Nokho, just because something has been practiced for many years does not in itself grant it legitimacy. As a community; as women; as human beings; we should all embark on questioning those practices that advocate for the infliction of udlame emalungwini omphakathi wethu asengozini enkulu futhi enganakiweies. Like Black on Black violence, as a community, we should be willing to engage in dialogue that openly identifies and addresses those practices/issues that have detrimental effects.

I am not of the belief that these women who practice Breast Ironing on their young daughters, nieces, grandchildren etc. do so because they are inherently evil or to purposely destroy the lives of these young women. In fact, I do believe their actions are genuinely guided by their desire to protect their daughters. It is what they themselves have been thought and what they know. They too have been victims; however, the cyclical, generational nature of the practice has also transformed them into perpetrators. While some have advocated for the criminalization of the practice and the imposition of fines/jail sentences for Breast Ironing practitioners, I do not believe this will prove to be an effective deterrent. Kunalokho, we should engage in dialogue with these women. We should embark on policies and practices geared towards educating and empowering both the elders of the practice as well as the young victims. Like us, they are human beings and given their genuine love and desire to protect their children against potential harm, their acquisition of the relevant knowledge will be an effective tool in bringing about real change.

Posts Latest by Nekita (bheka konke)

- Ngaphambi Rihanna kwakukhona Grace Jones - December 27, 2014

- Marimba: Expression of Freedom, kodwa my Afro-Ecuadorians… - December 25, 2014

- Ngubani Eyenza Claim Zokuba the Capital Reggae of the World? - December 24, 2014